- Home

- Cynthia Huntington

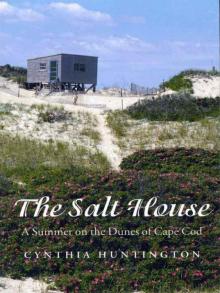

The Salt House

The Salt House Read online

The Salt

House

A Summer on the Dunes of Cape Cod

Cynthia Huntington

DARTMOUTH COLLEGE PRESS

Hanover, New Hampshire

Published by University Press of New England

Hanover and London

DARTMOUTH COLLEGE PRESS

Published by University Press of New England,

One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766

www.upne.com

© 1999 by Cynthia Huntington

First Dartmouth/University Press of New England paperback edition 2003

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Members of educational institutions and organizations wishing to photocopy any of the work for classroom use, or authors and publishers who would like to obtain permission for any of the material in the work, should contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766.

ISBNS for the paperback edition:

ISBN-13: 978-1-58465-294-6

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-61168-317-2

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Parts of this work originally appeared in slightly different form in: “The Spiral,” in A Place Apart: A Cape Cod Reader, edited by Robert Finch for W. W. Norton, July 1993; and “Euphoria,” in Provincetown Arts, Summer 1998.

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF NEW ENGLAND

publishes books under its own imprint and is the publisher for Brandeis University Press, Dartmouth College, Middlebury College Press, University of New Hampshire, Tufts University, and Wesleyan University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Huntington, Cynthia, 1951–

The salt house : a summer on the dunes of Cape Cod / Cynthia Huntington.

p. cm.

ISBN 0–87451–934–9 (alk. paper)

1. Huntington, Cynthia, 1951– —Homes and haunts—Massachusetts— Cape Cod. 2. Women poets, American, 20th century Biography. 3. Cape Cod (Mass.)—Social life and customs. 4. Natural history— Massachusetts—Cape Cod. 5. Sand dunes—Massachusetts—Cape Cod. 6. Cottages—Massachusetts—Cape Cod. 7. Summer—Massachusetts— 1. Title.

Ps35558.U517Z49 1999

99-20680

811.54 dc21

[B]

For Hazel Hawthorne Werner

The wilderness and the solitary place shall be glad for them; and the desert shall rejoice, and blossom like the rose.—ISAIAH 35:1

Contents

Preface

May

1. The Spiral

2. Dreamers

3. Waves

4. The Edge

5. Harrier

June

6. Nesting

7. Mouse in House

8. The Garden

9. Beach Rights

10. Beach Roses

11. Jacob’s Ladder

12. A Visit to Zena’s

13. The Thicket

July

14. Beach Days

15. At Evening

16. Sanctuary

17. Dog Days

18. Talking in the Dark

19. Tempest

20. Staying In

21. Fishers

August

22. Meridian

23. At Leisure

24. Sitting Down to Supper

25. Night Lights

26. Another Fish Story

27. A Late Walk

September

28. The Star Flower

29. Wild Fruits

Preface

For three summers I lived with my husband, Bert Yarborough, on the back shore of Cape Cod in a dune shack two hundred yards above the beach, on land owned by the National Park Service. “Dune shack” is the local, and by no means disparaging, term for a certain generation of beach cottages set along the two-mile dune ridge that runs between Race Point in Provincetown and High Head in North Truro, in what used to be the Provincelands State Reservation. Up into the 1920s, the Coast Guard maintained a Life Saving Station near here at Peaked Hill Bars. Many of the shacks were built by the guardsmen as places to bring their wives or girlfriends during their tour of duty, and were later passed down from friend to friend, and sometimes even sold, without regard to who actually owned the land beneath them. They lie along the ridge of the Peaked Hills, at the edge of the dune country that stretches between Route Six and the Atlantic Ocean, at the very tip of the Cape.

Though technically unsanctioned, building on public lands was never considered much of a problem on this part of the Cape. In fact, until near the end of the last century more than half the houses in Provincetown sat on land deeded to the original Plymouth Colony in 1650; in 1893 the state conceded the land beneath the village to its residents. When the Park Service took over jurisdiction of the newly formed Cape Cod National Seashore in 1961, it recognized this tradition of squatter’s rights by granting lifetime tenancy to the owners of the shacks. Often built with scrap wood and timbers salvaged from shipwrecks, uneven and raw, wobbly, frequently of eccentric design, they seem unlikely candidates to have endured the ravages of wind and time, yet perhaps a dozen or so still remain in use, continually patched and mended, shingled, shored up, and shoveled out. They remain so for as long as their owners, now grown old, continue to draw breath; they then pass into the hands of the Park Service. Tucked into the hills along the coastline, their roof peaks rising at careful distances from one another, each is a separate kingdom, holding on to its single history, as on to the shifting sand.

The Cape reaches out into the Atlantic from the Massachusetts coast due east for thirty miles, takes a ninety degree turn at Chatham, then proceeds north, flexing in toward the coast as it advances. At Truro the land begins to pull around to form a hook, turning to face the mainland at Race Point and continuing on south and east to Provincetown. Though most of the peninsula sits on a bed of rock left by the last glacier, this final hook is nothing but sand, built up over the past six thousand years from deposits washed along shore by storms and tides. This is where we lived, on no solid ground, at the extreme tip end of the continent, on a bare coast facing north to Greenland. It is a place set apart and bounded by water, where you look west to the coast of North America and the sun rises and sets from the sea. This outpost draws to it various migrants and drifters, sea birds, storm wrack, and tides’ leavings, and it was where our life together began.

A great beach, facing the Atlantic for forty miles from Provincetown to Monomoy, finds its endpoint here. The Peaked Hill Bars lie just offshore, extending their deadly shoals for miles out into the ocean. “Mallabarre,” Champlain called this coast when he explored it in 1608. Hundreds of ships have wrecked on these bars; their timbers lie buried in the sand. Behind this beach rise eight square miles of dunes and sand plains. All this land is wild, set free by wind and dotted with low growth, lying open under the sun. You step off the highway into the woods and walk a short way between scrub oak, huckleberry, and pitch pines, then you begin to climb a wall of sand. Huge drifts the color of raw silk rise, one beyond another, and the sky is an endless blue. On a hot day, the wavery light rising off the dunes suggests even vaster spaces, deserts of dream floating upward, a moonscape littered with scraps of bone and shell, loomed by cloud shadows, and at the end of it all lies the shining Atlantic, rolling up in scalloped waves against the beach.

Reading over these chapters, taken from our third summer in the dunes, they seem to me a record of some of the richest days of my life. The outer beach sees constant change, exposed to all weathers, tides, and seasons. These pages offer a sort of c

alendar of our life there, a life that was simple and spare, though never far removed from what we call civilization, in a place of such wild, austere beauty that at first I had no words for its spaces, its dusty heat, the thrilling clarity of its air. Only gradually was I able to take it into myself and let it remake me. My memories of those days are salt, clean and sharp. Days of light and water, salt air, the salt white dunes, the bite of seawater on my skin. Years later, I carry them all in my body, distilled in memory and circulated in the blood.

Bert and I first moved to the dunes ten days after we were married by a justice of the peace in the front room of a rented house in Provincetown, a union even our closest friends predicted would last six months at best. It is possible that bets were taken, though I lack any hard evidence for that suspicion. Never mind, what we had was between us, and we meant not so much to prove anyone wrong as to glide past all predictions into a new adventure. Ours was a quick romance between two people with no discernible plans for the future. Bert is an artist and I am a writer, and we meant to make that the basis of our life together, to invent a life out of what we knew and hoped to discover, making it up as we went along. It was in the dunes where our marriage began, where we learned to love long as well as hard, to live together side by side and work and play. This one-room shack was our only home in those first years—every fall we searched out an offseason-rental, and when spring came we packed ourselves back to the dunes. And so in that sense we thought of it as ours, without ever feeling that we could own it.

It seems to me that the greatest adventure is to find a home in the world, particularly in the natural world, to earn a sense of belonging deeply to a place and to feel the deep response well up within you and become a part of you. When it is done, it can’t be lost; the knowledge is as acute and sure as falling in love. What follows is a description of home. We took up residence, not by imposing ourselves on this place, but by giving ourselves over to it and learning what was truly ours.

What was ours was all around us, touching every sense. Glittering beach grasses, and the crying of the terns from dawn to midday, the light and empty spaces of the dunes and the pale line of beach stretching off to the horizon, the constant pounding of the waves, fierce ocean storms that came in and broke over us, and the image of the night sky, endless and bright, coming down to touch the ground all around—all these are deeply ingrained in my being. Days of solitude, walking the shore or writing at my desk under the back window, evenings together in the gentle shadows of the oil lamps—these I will always have. Intimacy with one other, and sometimes terrible silences born of fear or impatience as we learned to live together in a fragile balance of solitude and familiarity. In those rich seasons, if I was unhappy, and, incredibly, I was at times, the fault was in myself, in not being equal to all that was around me.

All of this, everything I have described here, is still as we left it. Who will live there now? Who will see it again? For us, the way our lives are measured, time seems to go forward, but in the wider world it circles and returns. You could go there today and find the same sky, the same waves, the identical birds. It could be yours as it is mine.

More than ten years have passed since we first went to live on the back shore of Cape Cod. As I write this, it is a winter night in New Hampshire, and I am sitting at my desk under bright electric lamps, thinking of the dunes. This night is so cold the thermometer dives below the mind’s rational limit of zero, as if it were only possible to gauge negative possibilities of warmth. The snow is piled on the roofs of the houses, and the road snakes black and gleaming between nine-foot drifts pushed up by the plows. The doors of our house are shut and locked, the storm windows fastened, the damper closed in the chimney. Yet even now the surf continues to pound up against the shore, and winter birds circle painfully over the breaking waves. The dunes are locked in their majestic silence, a reticence not of winter, but of eons. The great horned owl rises up from his nest in the oak tree and wheels above the frozen beach, and the shack stands shuttered and small, buffeted by wind, enclosing its dark inner space.

May

What shall I say about Salt House—isolated as a ship, and silent, with the living silence of an audience, though at the same time filled with the unceasing fluid articulation of the sea.

I want to say something important about it, that it has an insistence to drama, exactly in the way that each object stands out in the manner of an arranged and painted still-life… The commonplace is defeated here, by I know not what strangeness. Once across the dunes we live in an exquisite unreality.

HAZEL HAWTHORNE,

Salt House, 1934

ONE

The Spiral

We live on the inside curve of a spiral, where the peninsula turns around on itself and curls backward. The tip of this peninsula is still building, extending in a thin line as waves wash sand along the outer shore, nudging it north and west. Moving inward, counterclockwise, the spiral winds backward, to set this place apart in its own self-willed dreaming.

Out here beyond the last bedrock, past the crust of the glacial deposit, we live on a foothold of sand that is constantly moving. Everything eroded and nudged along shore ends up here, broken. Whole coastlines, boulders, good earth perhaps: they all arrive at last as sand. Sand keeps its forms barely longer than water; only the most recent wave or the last footprint stays on its surface.

Sleeping, we wake to sounds of water. Day and night the ocean mutters like a restless dreamer. We live beside it and sleep falling into its voices. Repeating, obsessive, the waves’ syllables might almost become words, but do not, just as the sand pushed back and forth at the tide line will not quite hold a form, though the ocean molds it again and again.

At night the oil lamps shine on the boards, and windows hold the flames in their black pools, yellow and welcoming if you were returning here after some journey. The only other lights glimmer down past the beach where boats sail into the night sky; the furthest ones blink like low stars on the horizon. Then one star may take flight, glowing yellow or red or green, and turn out to be a small plane patrolling this outpost, scanning the black water with its radar. The shack rocks gently in wind. Set up on wood pilings against the second dune, it lets the wind under it, gently lifting. We lie apart in narrow bunks like shipmates, breathing softly. Bert turns in his sleep, smacking the mattress with an outflung arm, and the whole bed shakes and resettles. In the high bunk, I feel the shack sway like a boat at anchor, and I know there is nothing fixed or steady, only these currents carrying us along in the dark. The windows are effacing themselves now, as the inner and outer darkness meet at the surface of the glass. I can still see a little bit of sky there; I lift my hand to touch the rough boards of the ceiling, pierced by the sharp points of shingle nails. The boards quiver slightly as night winds blow across them. Wobbling on its axis, the planet twirls off in space, spun in thrall to a star. Only the pull of that great fire, and our opposite thrust away from it, hold us on course.

We live on the outermost, outward-reaching shore of Cape Cod, at no fixed address. In the past three years we have lived in a series of rooms: summer houses in winter, apartments carved out of old hotels, a studio over a lumber yard, all borrowed nests. Of all the borrowed places, this one is best, a little board shack stuck up on posts in the sand, surrounded by beach roses, beach grass and miles of dunes, anchored in sand that flows straight down into the sea.

The shack has a name, Euphoria, which at first struck me as a little silly and high-flown. It means elation, and has to do with the wind. The name came with it, along with other bits of history. In its present incarnation it is the property of Hazel Hawthorne Werner, who holds a lifetime lease with the Cape Cod National Seashore, where it stands. Hazel bought Euphoria in the 1940s from a woman from Boston who had come out to join her lover, who had another shack a ways down the beach. He camped in that shack and she camped in Euphoria until the war came and he went off to fight. The woman from Boston bought it, years before that, from a Coa

st Guardsman who had built it to house his wife on summer visits. Story has it, she saw the place and promptly fled to town.

Hazel wrote a novel about her life in the dunes in a shack she called Salt House. I like that name, the way it distills the airy ecstasy of Euphoria to something more elemental, a flavor sharper than wind or spirit, preserving the body of the world in something hard and white. The taste of salt is always on my tongue here, held in the air and on every surface, beading my skin. The air has a flavor, a bite; even the sun has edges, reflected and magnified by sand and water. We see more clearly, taste and feel, here inside the salt house of our bodies.

A single room of unfinished boards, Euphoria measures about twelve by sixteen, with a narrow deck in front, facing east, a wall of windows looking north, and a weathervane on a knobby pole, that twirls like crazy in the constant winds. The shack is unpainted except for a little sky-blue trim on the screen door and along the eaves. The rest is the color of old wood—I should say colors, sometimes grey or silver, sometimes brown, depending how much damp is in the air and how the light falls. There are gaps between the boards, and around the doors and windows where sunlight and rain leak in equally; you can look down at the floor and see light glancing through. So it is a not-quite substantial shelter, the idea of a house, but with none of a real house’s constriction.

Inside are three tables, one under each window, bunk beds, a gas stove for cooking, and a wood stove for heat. We are equipped with six oil lamps, an enormous kettle bestriding both burners of the range, a dry sink, and a propane refrigerator which invariably breaks down in the heat of August. The front wall faces north across the Atlantic with two big windows we open by tugging on a rope slung over a pulley. Along the south wall another window gazes at the back end of a dune which is slowly collapsing toward the rear of the shack, held back by roots of bay and poison ivy. Day blows straight through when these windows are open, ruffling newspapers and sending loose papers flying. In the most sheltered corner, by the cookstove at the foot of the bunks, a high, narrow window catches the last light of sunset glinting on upended pots and pans drying in the dishrack after supper.

The Salt House

The Salt House